Plot Summary

Sinusitis, Sorcery, and Sympathy

The narrator, suffering from sinusitis, is regaled by George with a tale of two opticians, Manfred and Absalom, who fall for the same woman, Euterpe. Their friendship is tested by love and illness, but George, with the help of his tiny demon Azazel, tries to cure Manfred's colds. The cure backfires: Euterpe chooses Absalom, drawn by his vulnerability, not Manfred's newfound health. The story is a wry meditation on unintended consequences, the limits of intervention, and the unpredictable nature of love and human desire, all wrapped in Asimov's signature humor and gentle irony.

Love, Criticism, and Curses

George recounts the tragicomic romance of Lucius Hazeltine, a critic, and Agatha Lissauer, a writer. Their professions doom their love, as each is bound by oaths to criticize or resist criticism. Azazel's magic swaps their roles—critic becomes poet, writer becomes critic—but the result is only more suffering. Their love remains unfulfilled, each tormented by the other's new profession. The tale lampoons the eternal struggle between creators and critics, the futility of changing human nature, and the inescapable cycles of professional and personal misery.

The Jobless Prince's Dilemma

Vainamoinen "Van" Glitz, wealthy and idle, is challenged by his beloved Dulcinea to get a job to prove his worth. Despite Azazel's magical help, Van is unsuited for work, and Dulcinea's ambitions soon redirect her to politics, with Van as her supportive spouse. The marriage becomes Van's "job," a role he cannot escape, leaving him drained and unfulfilled. The story satirizes gender roles, societal expectations, and the paradoxes of ambition, showing how even magical solutions cannot resolve the deeper conflicts of identity and purpose.

Cold Hearts, Warm Hands

Euphrosyne, a shy woman who marries for cash, finds herself unable to reciprocate her husband Alexius's affections. Azazel's intervention makes her perpetually cold, driving her into Alexius's arms for warmth. Their marriage becomes unexpectedly passionate, but Euphrosyne's attempts to find warmth elsewhere fail—only Alexius suffices. The story explores the transformation of relationships, the unpredictable effects of magical meddling, and the way love can emerge from the most unlikely circumstances, blending humor with a gentle critique of materialism and emotional repression.

Time's Wounds and Regrets

Fortescue Flubb, a successful author, is haunted by the scorn of a high school teacher. Azazel offers a vision of time travel, allowing Flubb to confront his tormentor, but even in fantasy, the teacher remains unmoved. Flubb's honest self-awareness prevents him from rewriting the past to his satisfaction. The story is a poignant reflection on the persistence of old wounds, the limits of revenge, and the necessity of accepting one's history, no matter how painful or unresolved.

Wine, Wisdom, and Woe

Cambyses Green, charming but perpetually drunk, is loved by Valencia, who wishes he would sober up. Azazel grants Cambyses a connoisseur's palate, making all but the finest drinks intolerable. Cambyses becomes cold, critical, and joyless, alienating Valencia and himself. The tale is a darkly comic meditation on the dangers of "fixing" people, the complexity of addiction, and the way virtues, when taken to extremes, can become vices. Asimov's wit underscores the tragicomic nature of self-improvement gone awry.

Mad Science, Broken Dreams

Martinus Dander, a brilliant but unrecognized physicist, seeks validation for his revolutionary theories. With Azazel's help, his work is published, but it is riddled with errors, and he becomes a laughingstock. Driven to madness, Dander contemplates catastrophic experiments. The story is a cautionary tale about the perils of unchecked ambition, the cruelty of academic gatekeeping, and the fine line between genius and madness. Asimov deftly balances satire and pathos, highlighting the human cost of scientific obsession.

Three Princes, One Heart

In the kingdom of Micrometrica, three princes—Primus, Secundus, and Tertius—compete for the hand of Princess Meliversa, who turns suitors into statues if they fail. The first two rely on strength and skill, but only Tertius, with kindness and poetry, wins her heart. The princess, disguised as a serving maid, tests the princes' true natures. The story is a gentle subversion of fairy tale tropes, celebrating empathy, humility, and the value of inner qualities over outward prowess.

Corporate Songs, Hollow Victories

Cuthbert "Cussword" Culloden, tasked with instilling "corporate enthusiasm" at B & G, uses Azazel's magic to make his motivational songs irresistible. The company becomes a carnival of joy, but productivity collapses and bankruptcy follows. The story lampoons corporate culture, the emptiness of forced positivity, and the dangers of manipulating human nature for profit. Asimov's satire exposes the absurdities of modern work life and the futility of seeking easy solutions to complex problems.

Batman's Butler and Misunderstandings

Bruce Wayne, the real-life inspiration for Batman, recounts a troubling episode: his butler Cecil, entrusted with valuable memorabilia, calls to say he's "going northwest," prompting Wayne to wait in North Dakota. Cecil returns safely to New York, and only later does Wayne realize "northwest" referred to the airline, not the direction. The misunderstanding strains their relationship until an outsider clarifies the confusion. The story is a lighthearted exploration of communication, trust, and the human tendency to overcomplicate simple matters.

Clumsy Prince, Flameless Dragon

Prince Delightful, cursed with gracelessness by the well-meaning fairy Misaprop, sets out to slay a dragon to win Princess Laurelene. The dragon, Bernie, is similarly afflicted—unable to breathe fire, he emits a noxious stench. Together, they defeat an enemy army and win the princess's hand. The story is a playful inversion of fairy tale conventions, celebrating the virtues of imperfection, the power of friendship, and the serendipity of mismatched destinies.

Magic, Technology, and Wonder

Asimov reflects on the relationship between magic and technology, arguing that sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, but true magic is limitless, unconstrained by the laws of physics. He explores the allure of magical thinking, the human desire for power without cost, and the necessity of limits in science. The essay is both a celebration of imagination and a sober reminder of reality's boundaries.

Swords, Sorcery, and Stupidity

Asimov critiques the sword-and-sorcery genre, tracing its roots to ancient myths and lamenting its glorification of brute strength over intelligence. He contrasts this with science fiction's emphasis on reason and problem-solving, arguing that true heroism lies in the use of intellect. The essay is a thoughtful analysis of genre conventions, cultural values, and the enduring appeal of both muscle and mind.

Tolkien's Ring and Modernity

Asimov examines Tolkien's masterpiece, interpreting the Ring as a symbol of industrial technology—powerful, addictive, and destructive. He explores the novel's themes of good versus evil, the dangers of unchecked progress, and the longing for a lost, pastoral world. The essay situates Tolkien within the broader context of fantasy literature and reflects on the enduring relevance of his work in an age of environmental crisis.

Knights, Giants, and Myths

Asimov traces the origins of knights, giants, and other mythic figures, exploring how historical realities are transformed into romanticized archetypes. He discusses the social functions of these stories, their role in shaping cultural identity, and their persistence in modern fantasy. The essay is a meditation on the power of narrative, the construction of heroism, and the ways in which myths both reflect and distort reality.

Fantasy's Birth and Purpose

Asimov charts the development of fantasy as a literary genre, distinguishing it from science fiction and tracing its roots to ancient myths, religious texts, and folk tales. He argues that fantasy emerges when societies begin to recognize the difference between the possible and the impossible, and that its enduring appeal lies in its ability to explore the limits of imagination. The essay is a celebration of creativity, skepticism, and the human need for stories that transcend reality.

Criticism, Fantasy, and Inclusion

Asimov reflects on the role of criticism, the boundaries between genres, and the importance of inclusivity in literature. He defends the publication of fantasy alongside science fiction, arguing that both genres serve the imagination and that rigid definitions stifle creativity. The essay is a call for openness, tolerance, and the recognition of value in all forms of storytelling.

Thinking, Ignorance, and Human Difference

Asimov addresses the challenges of scientific illiteracy, the limitations of intelligence testing, and the dangers of racism and exclusion. He argues for the value of diversity, the necessity of critical thinking, and the importance of humility in the face of human complexity. The essay is both a critique of societal failings and a hopeful vision of a more enlightened, inclusive future.

Characters

George

George is the recurring narrator's friend, a charming deadbeat with a penchant for meddling in others' lives through the magical interventions of Azazel. He is both comic and tragic, embodying the human desire to help and the folly of unintended consequences. George's relationships—with friends, lovers, and Azazel—are marked by affection, exasperation, and a deep-seated need for validation. Psychologically, he is a mix of self-deprecation and sly manipulation, always seeking advantage but rarely finding satisfaction. His development is circular: each story finds him unchanged, yet subtly more aware of the limits of his power and the complexity of human nature.

Azazel

Azazel is a two-centimeter extraterrestrial or demon, summoned by George to perform magical favors. He is irascible, vain, and easily flattered, but his interventions invariably backfire, exposing the unpredictability of tampering with fate. Azazel represents the dangers of wish fulfillment and the limits of power without wisdom. His relationship with George is transactional, marked by mutual exploitation and grudging respect. Psychologically, Azazel is both omnipotent and impotent, a symbol of the gap between desire and reality.

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator is George's foil, a rationalist who is both fascinated and appalled by George's stories. He provides a grounding perspective, questioning the logic and morality of magical interventions. His relationship with George is ambivalent—part friendship, part rivalry, part exasperation. Psychologically, he embodies skepticism, caution, and a deep-seated need for order in a chaotic world. Over time, he becomes more resigned to the absurdities of life, finding humor and pathos in the failures of both magic and reason.

Manfred Dunkel

Manfred is a skilled optician whose friendship with Absalom is tested by their mutual love for Euterpe. His struggle with illness and his principled refusal to sabotage his rival reveal a deep sense of honor and vulnerability. Psychologically, Manfred is driven by a need for fairness and recognition, but his inability to adapt to the irrationalities of love leads to loneliness and regret. His development is marked by resignation and a bittersweet acceptance of fate.

Absalom Gelb

Absalom is Manfred's friend and competitor, equally skilled and equally smitten with Euterpe. His physical grace and musical talent make him the favored suitor, but his own vulnerabilities—particularly his back problems—draw Euterpe's sympathy. Psychologically, Absalom is less introspective than Manfred, more comfortable with the messiness of life, and ultimately more successful in love. His relationship with Manfred is complex, blending camaraderie, rivalry, and mutual respect.

Euterpe Weiss

Euterpe is the catalyst for the conflict between Manfred and Absalom. Her attraction to vulnerability and her nurturing instincts drive the narrative, revealing the power of empathy and the unpredictability of attraction. Psychologically, she is both idealized and humanized, embodying the complexities of desire, compassion, and agency. Her choices shape the destinies of those around her, highlighting the limits of control and the importance of authenticity.

Lucius Lamar Hazeltine

Lucius is a literary critic whose beauty shields him from retribution but not from loneliness. His love for Agatha Lissauer is thwarted by professional obligations and personal pride. Psychologically, Lucius is torn between the need for connection and the demands of his role, unable to reconcile love and duty. His transformation into a poet only deepens his suffering, illustrating the inescapability of one's nature and the tragedy of unfulfilled longing.

Agatha Dorothy Lissauer

Agatha is a successful author whose embrace of criticism, after her romance with Lucius falters, reveals the corrosive effects of professional rivalry and personal disappointment. Psychologically, she is driven by ambition, pride, and a deep-seated need for validation. Her inability to escape the cycle of criticism and creation mirrors Lucius's plight, underscoring the futility of role reversal and the persistence of suffering.

Vainamoinen "Van" Glitz

Van is a wealthy, charming ne'er-do-well whose quest for purpose is derailed by his unsuitability for conventional work and his entanglement with Dulcinea. Psychologically, Van is passive, adaptable, and ultimately resigned to a life defined by others' ambitions. His journey is a satire of privilege, gender roles, and the search for meaning in a world that values productivity over contentment.

Dulcinea Greenwich

Dulcinea is Van's dynamic, driven beloved, whose insistence on work masks her own aspirations. Her transition into politics transforms Van's life, making him the "First Gentleman" and reversing traditional gender roles. Psychologically, Dulcinea is assertive, pragmatic, and unyielding, embodying the complexities of modern ambition and the challenges of partnership. Her relationship with Van is both empowering and suffocating, highlighting the tensions between love, power, and self-fulfillment.

Plot Devices

Magical Realism and Satire

Asimov employs magical realism, using Azazel's interventions as a plot device to explore human folly, desire, and the unintended consequences of wish fulfillment. The stories are structured as nested narratives, with George recounting tales to the skeptical narrator, creating a frame that allows for both humor and critical distance. Satire is used to lampoon social conventions, professional rivalries, and the absurdities of modern life, while magical elements expose the limitations of both reason and magic.

Role Reversal and Irony

Many stories hinge on role reversal—critics become writers, the jobless become indispensable, the cold become passionate—only to reveal the persistence of underlying character traits and the futility of external change. Irony pervades the narratives, as well-intentioned interventions lead to disaster, and characters' efforts to escape their fates only entrench them further. This device underscores the complexity of human nature and the unpredictability of outcomes.

Allegory and Metafiction

Asimov frequently uses allegory and metafiction, embedding commentary on literature, criticism, and genre within the narratives themselves. The stories are self-aware, often breaking the fourth wall to address the reader directly or to comment on the act of creation. This device allows Asimov to explore the boundaries between fantasy and reality, the power of narrative, and the responsibilities of both writer and reader.

Foreshadowing and Circular Structure

Foreshadowing is used to build anticipation and to highlight the inevitability of certain outcomes, while circular structures—stories that end where they began, or that return to unresolved questions—emphasize the persistence of human flaws and the limitations of intervention. These devices create a sense of unity across the diverse stories, reinforcing the central themes of consequence, irony, and the search for meaning.

Analysis

Isaac Asimov's Magic: The Final Fantasy Collection is a masterful blend of satire, fantasy, and philosophical reflection, using the recurring device of magical intervention to probe the deepest anxieties and aspirations of modern life. Through the misadventures of George, Azazel, and a cast of vividly drawn characters, Asimov exposes the folly of seeking easy solutions to complex problems, the dangers of wish fulfillment, and the enduring power of human nature to confound even the most well-intentioned plans. The collection is both a celebration and a critique of fantasy itself, exploring the boundaries between magic and technology, the allure of escapism, and the necessity of limits in both art and life. Asimov's wit and compassion shine through every story, inviting readers to laugh at the absurdities of existence while also confronting the pain of regret, the persistence of prejudice, and the challenges of love and ambition. Ultimately, the collection is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the value of humility, and the transformative power of imagination. In a world increasingly defined by uncertainty and change, Asimov's final fantasy reminds us that magic—whether technological, emotional, or narrative—can illuminate our lives, but only if we are willing to accept its limits and embrace the complexity of our own humanity.

Last updated:

Review Summary

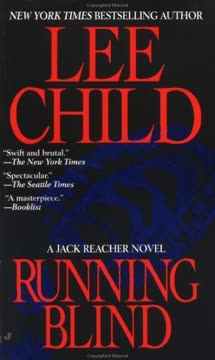

Magic by Isaac Asimov receives mixed reviews, averaging 3.64/5 stars. The book contains three parts: short stories (primarily the George and Azazel series), essays on fantasy, and general essays on various topics. Many readers found the title misleading, as the content feels more science fiction than fantasy. The Azazel stories are formulaic but amusing, while some reviewers preferred the nonfiction essays, which address topics like Tolkien, education, racism, and intelligence. Several readers note Asimov's logic-driven approach prevents him from fully embracing fantasy. Fans appreciate his wit and insight, though some found the collection hodgepodge and disappointing.