Plot Summary

Wounded Inspector's Awakening

Inspector Salvo Montalbano awakens in the dead of night, haunted by the trauma of a recent gunshot wound and the emotional aftershocks it has left behind. Livia, his partner, tends to him with a mixture of tenderness and firmness, but Montalbano is unsettled by his own vulnerability. The physical pain in his shoulder is matched by a new, embarrassing sensitivity—tears come easily, and he is forced to confront his own mortality. As he recovers, he reflects on his relationships, his possessions, and the people who matter most to him, all while feeling the world has paused at the moment of his injury. The inspector's convalescence is marked by a sense of stasis, introspection, and the first hints of a new case that will soon demand his attention.

Shadows Over Marinella

Despite his doctor's orders to rest, Montalbano is unable to detach from his work. The tranquility of Marinella is shattered by a series of phone calls that drag him back into the world of crime and investigation. Livia's presence is both a comfort and a source of tension, as she struggles to keep him from overexerting himself. The inspector's colleagues, Fazio and Catarella, keep him informed of developments, and the outside world begins to intrude on his fragile peace. The sense of unease grows as Montalbano is drawn, almost against his will, into a new mystery that will test both his physical limits and his emotional resilience.

The Vanished Student

Susanna Mistretta, a bright university student, vanishes on her way home from a study session. Her abandoned motorbike is found near her family's villa, but there are no signs of struggle or clues to her whereabouts. The Mistretta family is plunged into crisis: her father, Salvatore, is a geologist worn down by years of hardship and his wife's terminal illness; her uncle Carlo, a doctor, steps in to help. Montalbano, still officially on leave, is compelled to investigate, sensing that the case is more complex than it appears. The community is gripped by anxiety, and the inspector's instincts tell him that the disappearance is not a simple kidnapping for ransom.

A Family in Crisis

As Montalbano interviews the Mistretta family, he uncovers layers of tension and unspoken pain. Salvatore is desperate and guilt-ridden, his wife Giulia is dying, and Susanna has been her primary caregiver. The inspector probes the possibility that Susanna ran away, but her father insists she would never abandon her family. The family's financial struggles are laid bare, and the inspector learns of a wealthy uncle, Antonio Peruzzo, who has been estranged from the family for years. The emotional weight of illness, loss, and pride hangs over the household, complicating the investigation and hinting at deeper wounds.

The Spider's Web Tightens

Montalbano and his team follow a series of confusing leads: the positioning of Susanna's motorbike, the absence of her helmet, and the lack of any ransom demand. The inspector's conversations with Susanna's boyfriend, Francesco, and her study companion, Tina, reveal little. The media seizes on the story, and public opinion begins to swirl. The inspector senses that the case is a carefully constructed web, with someone manipulating events from the shadows. The metaphor of the spider—patient, methodical, and unseen—emerges as Montalbano contemplates the nature of the crime and the mind behind it.

Suspicions and False Trails

The investigation is beset by false leads: Susanna's backpack and helmet are found in locations that seem designed to mislead. The police and Carabinieri search the countryside, but every clue appears to be a deliberate distraction. Montalbano grows increasingly convinced that the kidnappers are not professionals, but rather someone with intimate knowledge of the family and the area. The inspector's own emotional state is tested as he confronts the suffering of the Mistrettas and the limitations of his own methods. The case becomes a psychological battle, with the perpetrator always one step ahead.

The Ransom Demand

At last, a ransom demand arrives—a recorded phone call in which Susanna's desperate voice is heard, followed by a disguised male voice demanding six billion lire. The message is sent not only to the family but also to local television stations, ensuring maximum public exposure. The demand is oddly specific, and the use of lire instead of euros suggests an older perpetrator. The community is galvanized, and pressure mounts on Susanna's uncle, Antonio Peruzzo, to pay. Montalbano recognizes that the kidnappers are manipulating both the family and public opinion, using the media as part of their strategy.

Public Outcry and Private Pain

The case becomes a public spectacle, with journalists, politicians, and townspeople all weighing in. Peruzzo, a wealthy and controversial figure, is vilified for his apparent reluctance to pay the ransom. The Mistrettas are caught between pride and desperation, while Susanna's suffering is broadcast for all to see. Montalbano is frustrated by the intrusion of the media and the simplistic narratives being spun. The inspector's own relationship with Livia is strained by the emotional toll of the case, and he is haunted by the image of Susanna, alone and imprisoned, as the town's collective anxiety reaches a fever pitch.

The Uncle's Secret

Through persistent inquiry, Montalbano uncovers the tangled history between the Mistrettas and Peruzzo. Years earlier, Peruzzo borrowed a vast sum from his sister Giulia and her husband, never repaid it, and subsequently severed ties with the family. The inspector learns that Giulia's illness is rooted in this betrayal—a slow poisoning of the spirit rather than the body. The kidnapping, it becomes clear, is not about money alone but about revenge, justice, and the settling of old scores. The web tightens as Montalbano realizes that the crime is deeply personal, orchestrated by someone with intimate knowledge of the family's pain.

The Girl in the Vat

A photograph of Susanna, chained in a concrete vat, is sent to the media, confirming her captivity and escalating the pressure on Peruzzo. Montalbano's analysis of the photo reveals subtle clues: the setting is an old wine vat, the lighting is deliberate, and the message is carefully crafted. The inspector deduces that the kidnappers are staging a drama for public consumption, manipulating every detail to achieve their ends. Susanna's courage and determination are evident, but so is the calculated cruelty of her captors. The case becomes a battle of wills, with the inspector racing against time to unravel the truth.

The Town Turns

As the days pass, the town's anger toward Peruzzo intensifies. Rumors swirl, and the engineer's reputation is destroyed by a combination of media scrutiny and popular outrage. Even the church and local dignitaries join the chorus demanding that he pay the ransom. Peruzzo's attempts to clear his name are met with skepticism, and his political ambitions are dashed. The inspector observes the destructive power of collective judgment, as the community's need for a villain outweighs any concern for the truth. The case becomes a morality play, with Peruzzo cast as the spider at the center of the web.

The Money That Wasn't

Peruzzo claims to have paid the ransom, delivering a suitcase full of cash to a remote location as instructed. But when the police recover the bag, it is filled with worthless paper. The revelation shocks everyone: was Peruzzo trying to cheat the kidnappers, or was he himself deceived? Susanna is released unharmed, but the mystery deepens. Montalbano suspects that the entire kidnapping was a carefully orchestrated performance, with the real target not the girl but Peruzzo's reputation. The inspector is left to ponder the nature of justice and the limits of his own authority.

The Truth Unraveled

Haunted by doubts, Montalbano returns to the Mistretta villa and confronts Dr. Carlo Mistretta and Susanna. Through a series of probing questions, he reveals his suspicions: the kidnapping was staged by Susanna and her uncle as an act of revenge against Peruzzo. The clues—the placement of the helmet and backpack, the details in the photograph, the use of the family's own property—point to an inside job. Susanna's hatred for her uncle, born of her mother's suffering, is transformed into a cold, methodical plan. The inspector is moved by the purity of her motive and the price she is willing to pay.

The Price of Hatred

Susanna's confession is both a release and a burden. She has achieved her goal—destroying Peruzzo's reputation and avenging her mother—but at the cost of her own happiness. She breaks off her relationship with Francesco and resolves to leave for Africa, seeking redemption through service. Dr. Mistretta, complicit in the scheme, is left to grapple with his own guilt and the consequences of his actions. Montalbano, torn between duty and compassion, chooses not to expose them, recognizing the complexity of justice and the limits of the law. The web has been spun, but all its threads are stained with sorrow.

The Patience of the Spider

Alone on his veranda, Montalbano contemplates a spider's web glistening in the morning sun. The metaphor of the spider—patient, relentless, and unseen—captures the essence of the case and the human capacity for both cruelty and endurance. The inspector is struck by the imperfection at the heart of the web, a reminder that even the most carefully laid plans are flawed. He is haunted by the face he glimpsed at the center of the web, a fusion of victim and perpetrator, love and hate. The case has left him changed, more aware of the ambiguities of justice and the cost of vengeance.

Farewells and New Beginnings

Livia's vacation ends, and she returns to Genoa, leaving Montalbano alone in Marinella. Their parting is bittersweet, marked by conflicting emotions of love, relief, and regret. The inspector is left to reflect on his own aging, his solitude, and the choices he has made. The case has exposed the fragility of human relationships and the difficulty of reconciling personal conscience with professional duty. As he resumes his daily routines, Montalbano is acutely aware of the emptiness left by Livia's absence and the unresolved questions that linger in the wake of the investigation.

The Inspector's Choice

In the aftermath of the case, Montalbano is faced with a choice: to pursue justice as defined by the law or to honor the deeper truths he has uncovered. He chooses compassion, allowing Susanna and her uncle to go unpunished, recognizing that their crime was born of suffering and a desperate need for meaning. The inspector's decision is both an act of rebellion and an affirmation of his own humanity. As he watches the rain wash away the spider's web, he understands that true justice is as fragile and complex as the threads of the web itself—always imperfect, always in need of patience.

Characters

Salvo Montalbano

Inspector Montalbano is a man marked by both physical and emotional wounds. His recent injury has left him vulnerable, introspective, and more attuned to the suffering of others. He is fiercely intelligent, intuitive, and driven by a deep sense of justice that often puts him at odds with bureaucratic authority. Montalbano's relationships—with Livia, his colleagues, and the people he serves—are complex, shaped by his empathy and his struggle to balance duty with conscience. Throughout the case, he is both hunter and prey, ensnared in the web of human frailty and moral ambiguity. His ultimate decision to show mercy reflects his growth and his recognition of the limits of the law.

Livia Burlando

Livia is Montalbano's long-distance partner, a woman of strength, intelligence, and deep feeling. She cares for the inspector during his convalescence, providing both comfort and challenge. Their relationship is marked by love, frustration, and frequent quarrels, reflecting the difficulties of intimacy and the demands of Montalbano's work. Livia's presence forces the inspector to confront his own vulnerabilities and the cost of his choices. Her eventual departure leaves him acutely aware of his solitude and the emotional toll of his profession. Livia embodies the tension between personal happiness and the sacrifices required by love.

Susanna Mistretta

Susanna is a young woman shaped by suffering and a fierce sense of loyalty to her family. Her mother's illness and her uncle's betrayal have left deep scars, fueling a hatred that transforms into a calculated plan for revenge. Susanna's intelligence, courage, and determination are evident throughout her ordeal, but so is her capacity for sacrifice. She orchestrates her own kidnapping, enlisting her uncle's help to destroy Peruzzo's reputation and avenge her mother. In the end, Susanna chooses to leave her old life behind, seeking redemption through service in Africa. Her journey is one of transformation, from victim to agent of her own destiny.

Dr. Carlo Mistretta

Carlo is Salvatore's brother and Susanna's uncle, a doctor whose love for his family leads him down a path of complicity and guilt. He is haunted by his unrequited love for Giulia and his inability to save her from despair. Carlo's decision to help Susanna stage the kidnapping is driven by a mixture of loyalty, grief, and a desire for justice. He is both a protector and an enabler, willing to risk everything to right the wrongs done to his family. Carlo's actions force him to confront the limits of his own morality and the consequences of choosing personal loyalty over the law.

Salvatore Mistretta

Salvatore is a geologist whose life has been marked by hardship, loss, and the slow decline of his wife, Giulia. He is devoted to his daughter and wife, but powerless to prevent the tragedies that befall them. Salvatore's pride and sense of honor prevent him from seeking help, even as his family is torn apart. He is kept in the dark about the true nature of Susanna's kidnapping, suffering genuine anguish and fear. Salvatore embodies the pain of the innocent, caught in the crossfire of others' schemes and the inexorable march of fate.

Antonio Peruzzo

Peruzzo is the Mistrettas' wealthy but morally compromised relative, whose betrayal of his sister and refusal to repay a massive debt set the stage for the entire drama. Ambitious, calculating, and ultimately self-serving, Peruzzo becomes the target of Susanna's revenge and the focus of the town's collective anger. His attempts to clear his name and avoid responsibility only deepen his isolation and disgrace. Peruzzo's downfall is both a personal tragedy and a commentary on the corrosive effects of pride, greed, and the failure to atone for past wrongs.

Francesco Lipari

Francesco is Susanna's boyfriend, a law student whose love and loyalty are tested by her disappearance and subsequent rejection. He is intelligent, sensitive, and persistent, assisting Montalbano in the investigation and refusing to give up hope. Francesco's heartbreak at Susanna's decision to leave is palpable, and his questions about the meaning of her actions reflect the broader themes of loss, sacrifice, and the search for justice. He represents the collateral damage inflicted by the pursuit of vengeance and the difficulty of understanding the motives of those we love.

Giulia Mistretta

Giulia is the emotional center of the Mistretta family, her slow decline a symbol of the corrosive effects of betrayal and unhealed wounds. Her illness is described as a poisoning of the will to live, brought on by her brother's actions and the collapse of her family's fortunes. Giulia's suffering motivates Susanna's quest for justice and shapes the emotional landscape of the novel. Though largely absent from the narrative, her presence is felt in every decision and every act of love or vengeance.

Fazio

Fazio is Montalbano's trusted right-hand man, a steady and reliable presence throughout the investigation. He is methodical, observant, and deeply committed to his work. Fazio's insights and support are invaluable to the inspector, and his own emotional responses to the case reflect the broader impact of crime on those who seek to solve it. Fazio serves as a moral anchor, reminding Montalbano of the importance of compassion and the need to look beyond the surface of events.

Catarella

Catarella is the bumbling but well-meaning police officer whose malapropisms and misunderstandings provide moments of levity amid the darkness of the case. His loyalty to Montalbano is unwavering, and his innocence serves as a counterpoint to the cynicism and complexity of the adult world. Catarella's presence is a reminder of the enduring need for kindness, humor, and human connection in the face of suffering and injustice.

Plot Devices

The Spider's Web

The central plot device of the novel is the metaphor of the spider's web—a symbol of patience, cunning, and the slow, methodical construction of a trap. The kidnapping is revealed to be a carefully orchestrated scheme, with every detail designed to ensnare the true target: Antonio Peruzzo. The web is spun not by a criminal mastermind but by a victim seeking justice, and its threads are woven from the pain, betrayal, and endurance of the Mistretta family. The motif recurs throughout the narrative, culminating in Montalbano's contemplation of an actual spider's web, which serves as a meditation on the nature of justice, imperfection, and the human capacity for both cruelty and resilience.

False Leads and Red Herrings

The investigation is marked by a series of false clues—Susanna's helmet and backpack, the staged ransom demands, the misleading photograph—all intended to mislead both the police and the public. These red herrings heighten the suspense and force Montalbano to question his own assumptions. The use of misdirection reflects the psychological complexity of the crime and the intelligence of its perpetrators, who manipulate appearances to achieve their ends.

Psychological Realism and Moral Ambiguity

The novel employs a psychological approach to both character and plot, delving into the inner lives of the Mistrettas, Peruzzo, and Montalbano himself. The investigation becomes as much an exploration of motive and conscience as of physical evidence. The narrative structure is nonlinear, with frequent digressions, flashbacks, and introspective passages that blur the line between detective work and personal reflection. The resolution of the case is marked by moral ambiguity, as Montalbano chooses compassion over strict adherence to the law.

Media and Public Opinion

The media plays a crucial role in shaping the narrative of the case, amplifying public outrage and influencing the actions of both the perpetrators and the victims. The manipulation of public opinion becomes a weapon in the hands of the kidnappers, and the inspector must navigate the treacherous waters of rumor, spectacle, and moral panic. The interplay between private suffering and public spectacle is a recurring theme, highlighting the power and danger of collective judgment.

Foreshadowing and Symbolism

The novel is rich in foreshadowing and symbolic imagery: the recurring motif of the spider, the significance of time (the precise moment of Montalbano's injury), and the use of physical objects (the helmet, the photograph, the spider's web) to signal deeper truths. These devices create a sense of inevitability and interconnectedness, drawing the reader into the web of the narrative and inviting reflection on the nature of fate, justice, and human agency.

Analysis

Andrea Camilleri's The Patience of the Spider is a masterful meditation on justice, revenge, and the enduring scars of betrayal. Through the lens of a seemingly straightforward kidnapping, the novel explores the complexities of family, the corrosive effects of pride and guilt, and the limitations of the law. Montalbano's journey is as much internal as external, forcing him to confront his own vulnerabilities and the moral ambiguities of his profession. The metaphor of the spider's web—patiently spun, intricate, and ultimately imperfect—serves as a powerful symbol for the human condition: our capacity to endure suffering, to seek meaning in pain, and to act with both cruelty and compassion. The novel challenges the reader to question the nature of justice, the price of vengeance, and the possibility of redemption. In the end, Camilleri suggests that true justice is not found in the rigid application of the law, but in the patient, imperfect work of understanding, forgiveness, and the refusal to let hatred define our lives.

Last updated:

Review Summary

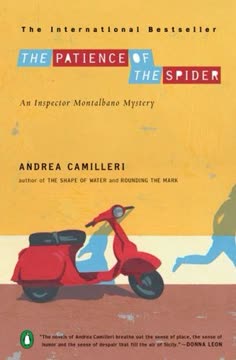

The Patience of the Spider follows Inspector Montalbano recovering from a gunshot wound while investigating a young woman's kidnapping. Readers praise Camilleri's humor, gorgeous Sicilian setting, and detailed food descriptions. Many found the mystery predictable but still enjoyed the journey, noting Montalbano's moral complexity and willingness to serve justice over strict law enforcement. The enforced downtime allows deeper character exploration as the aging inspector questions his career and relationships. Reviewers appreciate Camilleri's elegant prose, comedic situations, and ability to create compelling stories even without traditional murders.