Key Takeaways

1. The Genesis of Identity: From Jack Rosenberg to Werner Erhard

An impostor is someone with a fictitious past. The first thing to learn on the road to one's own true self is that one is not who one thinks one is.

A childhood of masks. Werner Erhard, born Jack Rosenberg in Philadelphia in 1935, experienced a complex childhood marked by family tensions and a series of violent accidents. These early traumas, including a near-fatal fall and a near-drowning, coincided with the Oedipus complex, suggesting unconscious patterns of self-punishment and a struggle for his mother's attention. His parents, Joe and Dorothy, a Jewish father converted to fundamentalist Christianity and an Episcopalian mother, created a home where religion was central but identity was fluid.

The burden of "doing the right thing." Jack's adolescence was shaped by an intense, yet often conflicted, relationship with his mother, Dorothy, whom he saw as both his muse and a dominating force. A lacrosse accident, where his mother's perceived indifference marked a turning point, led to a period of rebellion and a feeling of worthlessness. This culminated in an unplanned pregnancy with his girlfriend, Pat, leading to a marriage he felt burdened by, a "holocaust of one's experience on the altar of conformity."

Escape and new identity. Feeling trapped and operating from a "victim's position," Jack began a double life, adopting the name "Jack Frost" as a car salesman and engaging in affairs. In 1960, at 25, he abandoned his wife and four children, fleeing Philadelphia with June Bryde (who became Ellen Virginia). On a plane, he spontaneously chose the name Werner Erhard, creating a fictitious past to escape his old identity and the entanglement of his life, unknowingly carrying his unresolved patterns with him.

2. Early Education: The Power of Self-Image and Hypnosis

The core of their work is spiritual. What they say is, admittedly, not deep; but it is not silly either. If you don't master the issues that they are dealing with—personal competence and success—you will never be in a position to go more deeply.

Building a fortress of competence. In St. Louis, Werner and Ellen faced poverty and anonymity. Werner, determined to "beat the entanglement of life," immersed himself in self-help literature, particularly Napoleon Hill's Think and Grow Rich and Maxwell Maltz's Psycho-Cybernetics. These books, though often dismissed as "pop psychology," offered a "religion of self-motivation and self-reliance," teaching that:

- Ideas, freely created, are the source of all achievement.

- The mind transmutes dominant thoughts into reality.

- Autosuggestion and active imagination can implant positive thoughts.

Self-image as a control center. Maltz's concept of "self-image" resonated deeply with Werner. Maltz, a plastic surgeon, observed that internal self-image, not just external appearance, dictates behavior. He used cybernetics to explain how self-image acts as a "thermostat," regulating actions. To change habits, one must reset this internal thermostat. Maltz emphasized:

- Rejecting the "victim's position" and taking responsibility for one's self-image.

- Overcoming resentment, righteousness, and guilt, which fixate one in the past.

- The importance of physical relaxation, imagination, and hypnosis to create a new, positive self-image.

Breaking fixed reality. Werner applied these principles rigorously, practicing spiritual plastic surgery on himself and Ellen through autohypnosis and active imagination. He used hypnosis to address Ellen's fear of train whistles, uncovering a suppressed childhood trauma. These experiments, though initially focused on "tinkering with Mind," began to break down his "ordinary fixed reality," revealing the power of belief and the structures behind perception, laying groundwork for deeper insights.

3. The Human Potential Movement: Growth Beyond Motivation

The average man is a full human being with dampened and inhibited powers and capabilities.

From success to growth. In San Francisco (1962), Werner met Robert Hardgrove, who shifted his focus from mere motivation to human development, introducing him to Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. This marked a pivot from "personnel development to human development," recognizing that healthy, developing individuals are naturally successful. Werner attended early Esalen workshops, integrating motivational techniques with growth-oriented approaches like encounter and sensitivity groups.

Optimism and self-actualization. Maslow and Rogers, challenging traditional psychology's focus on pathology, championed an optimistic view of human nature. Maslow's study of "self-actualizing individuals" revealed common traits: accurate reality perception, self-acceptance, spontaneity, autonomy, and a high incidence of "peak experiences." They argued that basic human needs (food, safety, love, esteem) must be met for individuals to naturally pursue "meta-needs" like self-actualization, unleashing inherent potential.

Facilitative conditions and determinism. Rogers emphasized creating "safe spaces" and "facilitative conditions" for growth in therapy and groups, where individuals could reduce defensiveness and communicate openly. Both Maslow and Rogers rejected determinism, asserting human freedom and choice, a stark contrast to behaviorist views. Werner, though later developing a nuanced view on determinism, found in their work a powerful affirmation of individual agency and the possibility of transcending past conditioning.

4. Zen's Influence: Instantaneous Transformation and Non-Judgment

Of all the disciplines that I studied, practiced, learned, Zen was the essential one. It was not so much an influence on me; rather, it created space.

A clue to enlightenment. After a profound "peak experience" in Beverly Hills in 1963, which he initially mistook for enlightenment, Werner sought ways to understand and re-create it. Alan Watts, the English philosopher and Zen expositor, became a crucial guide. Watts opened Werner to the spiritual import of Oriental philosophies, particularly Zen, and introduced the critical distinction between "Self" and "Mind."

Zen's core tenets: Werner found in Zen a path to "instantaneousness leading to transformation, rather than process leading to change." Key aspects included:

- Emptying the Mind: Like Nan-in's tea cup, one must empty preconceived notions to truly see.

- Realizing inherent perfection: Every being is intrinsically whole and complete.

- Non-judgmental acceptance: Behaving non-evaluatively, granting "beingness" to all.

- Emphasis on the here and now: Not carrying the past or future, like Tanzan leaving the girl by the muddy road.

The Zen art of bookselling. Werner applied Zen principles to his sales organization, transforming it into a "laboratory" for human development. He taught his staff the "Zen art of bookselling," emphasizing communication over manipulation, integrity over sales tactics. This meant:

- Recognizing mothers' inherent commitment to their children.

- Creating a "safe space" for mothers to make choices without pressure.

- Being "unwilling to work without integrity," even if it meant losing a sale.

This approach fostered a loyal, high-intentioned staff, demonstrating that effectiveness could arise from a place of authenticity and non-attachment.

5. Scientology's Revelation: Mind as Machine, Self as Source

The most important theoretical insight that I got from Scientology concerned the Mind. I had been working to understand the Mind since the shift in my values following the peak experience in 1963.

Probing the disreputable. Werner fearlessly explored unconventional disciplines, including Subud and Scientology, seeking valuable notions and practices. His encounter with Scientology, through Mike Maurer and Peter Monk, provided a crucial theoretical breakthrough regarding the Mind. Despite its controversial nature and "ghastly" style, L. Ron Hubbard's work offered profound insights.

Mind as a reactive mechanism. Scientology, a form of "philosophical idealism," posits a godlike "thetan" (true Self) that creates and defines universes. Man's "fallen state" is entrapment in the "MEST universe" (matter, energy, space, time) due to the "reactive mind." This reactive mind is:

- A stupid stimulus-response mechanism.

- Run by traumatic "engrams" (painful past experiences).

- Continuously "restimulated" by present resemblances, causing automatic, unconscious reactions.

Werner accepted this characterization of Mind, seeing it as a machine rooted in positionality, the source of all trouble.

Duplication and imagination. Scientology's goal is to free the thetan from MEST entrapment. Key techniques include:

- Duplication: Consciously re-creating painful experiences to diminish their power.

- Rehabilitating imagination: Re-exercising creative ability to bring the reactive mind under control.

Werner found "auditing" (Scientology processes) to be the "fastest and deepest way to handle situations." He also experienced "memories" of past lives, which he interpreted as accessing archetypal patterns rather than literal past existences, further solidifying his understanding of Mind's mechanical nature.

6. The Freeway Transformation: A Direct Experience of Self

I was simply the space, the creator, the source of all that stuff. I experienced Self as Self in a direct and unmediated way.

The culmination of the quest. In March 1971, driving on a Marin County freeway, Werner experienced a profound transformation. After years of searching and disciplined practice, he found what he had been seeking. This experience was:

- Formless and timeless: Beyond language, emotions, or bodily sensations.

- A realization of knowing nothing, then everything: All prior knowledge, skewed towards survival and success, dissolved, revealing a "stupidly, blindingly simple" truth.

- An unmistakable recognition of Self: He realized he was not his emotions, thoughts, ideas, achievements, or identities (Jack Rosenberg or Werner Erhard), but "the space, the creator, the source of all that stuff."

Beyond identity and Mind. This transformation was a "contextual shift," moving his "ground of being" from Mind to Self. He understood that:

- All identities are false; he was the space of identities.

- His Mind, patterned unconsciously, was a machine, but he was not that machine.

- He was whole and complete as he was, the source of his experience.

This was not merely a "peak experience" (like 1963's conversion), but a fundamental shift in his ability to experience living, a "transformation" that transcended the limitations of Mind.

7. The Three Tasks of Transformation: Share, Own Ego, Clean Up Life

To share what had happened to me, and to take responsibility for my ego, I had to confront and to take responsibility for those things that Jack Rosenberg and Werner Erhard had done from an untransformed space.

Immediate consequences. The freeway transformation led to three immediate tasks for Werner:

- Share the experience: Not by giving it, but by creating an opportunity for others to realize they already possess it. This became the foundation of the est training.

- Take responsibility for his ego: Recognizing that "ultimate ego" is to believe one can function without ego. He could now use his "Werner Erhard" personality as an expression of Self, rather than being run by it.

- Clean up his life: Confronting and taking responsibility for past actions from an untransformed space, acknowledging the lies he told about himself and others.

Ellen's perspective on change. Ellen immediately noticed radical changes in Werner: he stopped smoking, drinking, coffee, and sugar, lost weight, and his demeanor mellowed. He then communicated openly with her about his past affairs and financial secrets, a true "first time" for their relationship. This honesty was possible because he no longer felt "stuck" in the marriage by his "Werner Erhard-the-man-of-his-word" position.

Transforming relationships. Werner realized he genuinely wanted to be married to Ellen. Their relationship had been a "racket" of him being the "bad guy" and her the "victim." To transform this, Ellen had to give up her victim role and become independent, which Werner supported by setting her up in her own business. Werner, in turn, had to become "willing for Ellen to succeed as my wife," accepting her as she was, without imposing his expectations. This process of mutual responsibility and acceptance led to a "joyful, effortless spontaneity."

8. The Est Training: An Econiche for Blowing the Mind

The est Standard Training is a new form of participatory theatre that incorporates Socratic method: the artful interrogation that is midwife at the birth of consciousness.

A siege on the Mind. The est Standard Training, launched in October 1971, was designed as an "econiche for transformation." It's a rigorous, irreverent, and intrusive "participatory theatre" that uses Socratic method to challenge the Mind. The goal is not a single "high" experience, but a contextual shift from a "deficiency orientation" to a "sufficiency orientation," transforming one's ability to experience living.

Uncovering unconsciousness. The training creates conditions to identify and examine:

- Mind structures: The organizing principles of Mind (survival, right/wrong, domination).

- Mind traps: Resentment, regret, righteousness, which reinforce positionality.

- Life programs: Specific unconscious beliefs, identifications, and fantasies.

- Repressed incidents: Traumatic memories blocked from awareness.

By observing these, participants expand beyond Mind, reducing the power of the past and moving towards a "here and now" state of completion.

The path to transformation. The training's four days progressively dismantle conceptual barriers. It uses:

- Presentations: Information, philosophical analysis, distinctions.

- Sharing: Participants communicate their realizations and problems.

- Processes: Exercises in imagination, often in altered states, to "experience out" conditions like headaches.

The "Truth Process" and "Danger Process" confront positionality and fear. The "Anatomy of the Mind" lecture is a cornerstone, leading participants to experience their Minds as machines, ultimately "blowing the Mind" and revealing the Self as the source of their experience.

9. The Morality of Transformation: Responsibility and Appropriateness

Responsibility, which is a way of experiencing life, is a level of abstraction that transcends "I did it," which claims a territory, as well as "I didn't do it." and "Somebody did it to me," both of which defend positions.

Beyond irresponsible morality. Werner's perspective introduces a distinctive morality rooted in transformation, contrasting with the "irresponsible morality" of the Mind state. Most conventional morality, he argues, is a form of politics, defending positions and seeking to control others. True responsibility, however, comes from the Self.

Being at cause. To be responsible means being willing to deal with any situation from the viewpoint that one is its source. This transcends:

- Fault, praise, blame, shame, or guilt.

- Judgments of good/bad, right/wrong.

- The positions of victim or hero.

A responsible person does not blame external forces, is not interested in revenge, and does not "hunger and thirst after righteousness." This abandonment of positionality is empowering, leading to strength and a focus on heightening the "aliveness of the matrix."

The art of appropriateness. Responsibility manifests as "appropriateness"—doing what is fitting or suitable to a situation, moment by moment. This requires being in the "here and now," without carrying over rigid "standards of appropriateness" from the past. Appropriateness is:

- Creative: Even when it means creating nothing.

- Effortless: It flows naturally as unconsciousness is removed.

- Control without force: It is simply "being there," akin to the Taoist concept of wu wei (nonaction without self-will).

This morality combats automaticity and positionality, fostering a life of conscious choice and expansion rather than contraction and reaction.

10. Social Transformation: Empowering Institutions for Aliveness

The world as it is, in an untransformed state, is evil. When using the word 'evil,' I do not mean what is ordinarily meant. What I mean by 'evil' is the selling or trading of aliveness for survival.

The "evil" of untransformed institutions. Werner asserts that the untransformed world is "evil," not in a moralistic sense, but as the "selling or trading of aliveness for survival." Existing institutions—government, education, etc.—often fail their stated purposes, instead excelling at justifying and perpetuating themselves, dominating others from the Mind state. This creates a restrictive "econiche" that is dangerous to individual transformation.

The need for transformed environments. Transformed individuals, having experienced aliveness, demand transformed relationships and institutions. Retreating from the world (like a monk to a cave) is seen as a "terrible waste," a manifestation of the environment's hostility to transformation. Werner's larger est program aims for a "revolutionary goal": to create conditions for transformation at all levels:

- Individual

- Family-relational

- Organizational-institutional

- Cultural-societal

Combating "going through the motions." Institutions foster positionality through:

- Lack of full communication.

- Pretense (socially sanctioned lying).

- Unacknowledged mistakes.

- Uncorrectability.

This leads to "ritual behavior" that is not "on purpose," creating effort, red tape, and dissatisfaction. Werner's own family and the est organization serve as ongoing experiments, meticulously frustrating "going-through-the-motions" behavior and implementing immediate correction and full communication, demonstrating that even "minor problems" are crucial.

11. Family Completion: The Prodigal Son's Return and Reconciliation

My mother and father, each in his or her own way, used the experience of the est training to expand his or her experience of love, happiness, health, and self-expression.

The return to Philadelphia. In October 1972, nearly 13 years after his departure, Werner returned to Philadelphia. His first call was to his uncle, Jim Clauson, followed by a reunion with his parents, Joe and Dorothy, and his siblings. Dorothy, who had suffered a 12-year depression, was initially shocked but then overwhelmed with joy. Joe, though initially irritated by Werner's absence, was deeply relieved.

Healing old wounds. Werner's return was marked by radical honesty. He openly discussed his past, his name change, and his reasons for leaving, without justification or blame. He simply "communicated clearly and acknowledged his responsibility," allowing his family to "discharge all the things that hadn't been said." This approach, informed by his transformation, allowed the family to:

- Release long-held resentments and guilt.

- Experience a profound sense of relief and reconciliation.

- Witness Werner's genuine love and affection, which had been suppressed.

A family transformed. Werner's siblings and first wife, Pat, also experienced profound shifts. Nathan, his younger brother, had a personal transformation during a phone call with Werner, realizing that true freedom came from embracing fear rather than avoiding it. Pat, initially wary, found her hatred for Ellen transform into friendship. By Thanksgiving 1974, the entire extended family, including Pat's parents, had taken the est training and gathered for a reunion, where they openly shared their lives and "cleaned up" old issues. This created "one big family," demonstrating that love, though previously "held down by all sorts of messy things," could now flourish.

12. The Enduring Lesson: You Can't Go West Forever

To be satisfied, to expand, you must first be where you are, and do what you're doing—no matter where you are and no matter what you are doing.

The futility of mere change. Werner's life story, marked by constant geographical and disciplinary shifts, illustrates the futility of seeking satisfaction through mere "change." He realized that "change is simply a variation on a theme; and the theme is some unconscious pattern in your relationship with your parents." These changes, though sometimes beneficial, were ultimately expressions of his dissatisfaction, not its solution.

Transformation recontextualizes change. True satisfaction and expansion come from "being where you are, and doing what you're doing—no matter where you are and no matter what you are doing." Transformation, by shifting one's context from Mind to Self, allows for genuine choice. Change, when it occurs from a place of satisfaction, becomes an expression of expansion and aliveness, rather than a desperate attempt to escape.

The gift of completion and forgiveness. Werner's completion of his relationships with his family was not about "forgiveness" in the conventional sense of condoning past wrongs. Instead, it was about "making space" and "self-forgiving and self-acceptance." By accepting himself, including his "bad" past, he created the possibility to truly be "good." This allowed him to accept his parents and family as they were, without judgment or resistance, fostering a relationship grounded in admiration and respect. His past no longer controlled him; he now "had his past," free to generate his own experience in the here and now.

Last updated:

Review Summary

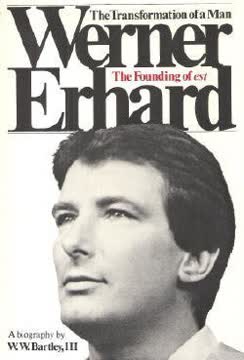

The Werner Erhard biography receives mixed reviews, averaging 3.93 stars. Supporters praise it as brilliant and transformational, particularly valuable for Landmark or EST graduates seeking insight into the program's origins. Critics note it's overly hagiographical and self-promoting, diminishing its effectiveness as objective biography. Readers appreciate learning about Erhard's complex journey from car salesman Jack Rosenberg to influential seminar leader, his philosophical approach blending American and Eastern thought, and his revolutionary vision for societal transformation. Most agree it's essential reading for understanding Landmark Education's foundations.