Key Takeaways

1. Darwin's Unanswered Question: The Arrival of the Fittest

Natural selection can preserve innovations, but it cannot create them.

Beyond selection. Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection brilliantly explained how advantageous traits persist and spread, but it left a crucial mystery unsolved: the origin of these innovations. He acknowledged that calling the source of new traits "random" was merely admitting ignorance. This gap in understanding, the "arrival of the fittest," remained a central puzzle for generations of scientists.

Time is not enough. Early 20th-century discoveries, like Ernest Rutherford's radiometric dating, expanded Earth's age to billions of years, seemingly providing ample time for random mutations to generate life's complexity. However, the sheer number of possible molecular configurations for even a single protein (e.g., 10^130 for a 100-amino-acid protein) makes a purely random search across cosmic timescales less likely than winning a lottery jackpot every year since the Big Bang.

The need for innovability. The existence of marvels like the peregrine falcon's eye or the intricate molecular machinery of a cell demands a principle that actively accelerates life's ability to innovate. This inherent capacity for innovation, termed "innovability," suggests that evolution is not solely a passive process of filtering random changes, but is guided by deeper, underlying natural principles.

2. Life's Innovations Emerge from Hyperastronomical Libraries

The deepest secrets of nature’s creativity reside in libraries just like this: all-encompassing and hyperastronomically large.

Vast possibility spaces. Imagine a "universal library" containing every conceivable combination of genetic information, from metabolic reactions to protein sequences and regulatory circuits. These libraries are "hyperastronomical" in size, meaning they contain far more "books" (genotypes) than there are atoms in the universe. For instance:

- Metabolic library: Over 10^1500 possible metabolisms (5,000 reactions, each present or absent).

- Protein library: Over 10^130 proteins (100 amino acids, 20 types).

- Regulatory circuit library: Over 10^700 circuits (40 genes, 3 interaction types).

Meaningful texts. Most "books" in these libraries are gibberish, representing non-functional or lethal biological systems. However, a tiny fraction are "meaningful," encoding viable metabolisms, functional proteins, or effective regulatory patterns. The challenge for evolution is to find these meaningful texts within an overwhelmingly vast space.

Combinatorial nature. Life's innovations are fundamentally combinatorial, assembling new functions from existing parts. Just as a jet engine combines a compressor, combustion chamber, and turbine, biological innovations combine:

- Existing metabolic reactions to process new toxins.

- Existing amino acids to form new protein shapes.

- Existing regulatory interactions to create new body plans.

3. Metabolism: Combinatorial Innovation from Primordial Soups to Poisons

Even before life itself arose, nature’s creativity used the same principles it uses today.

Early chemical creativity. Life's origin itself was an act of innovation, likely beginning with autocatalytic metabolic networks in environments like hydrothermal vents. These "primordial pressure cookers" provided:

- Concentration: Pores in mineral chimneys acted as tiny reaction chambers.

- Catalysts: Minerals like iron sulfide accelerated reactions.

- Energy & Materials: Abundant inorganic chemicals fueled early metabolism.

This suggests that the "arrival of the fittest" began even before the first self-replicating molecule.

The citric acid cycle. A prime candidate for the earliest metabolic innovation is the citric acid cycle, a network of reactions that:

- Is found in the oldest parts of modern metabolism.

- Can run in two directions (building or breaking molecules).

- Produces precursors for many of life's building blocks (amino acids, DNA parts).

- Is autocatalytic, meaning it makes more of itself.

Modern metabolic prowess. Over billions of years, metabolism has evolved into an incredibly versatile engine. Bacteria like E. coli can use over eighty different molecules as their sole source of carbon and energy, transforming poisons like pentachlorophenol into food. This is achieved by recombining existing enzyme-catalyzed reactions, demonstrating that metabolic innovation is an ongoing, combinatorial process.

4. Proteins: Shapely Solutions to Life's Diverse Challenges

The amino acid text of the Arctic cod’s antifreeze proteins didn’t originate in a single step, like Athena springing from the brow of Zeus.

Molecular workhorses. Proteins are the cell's primary workers, performing myriad tasks from catalyzing reactions (enzymes) to transporting molecules, contracting muscles, and regulating genes. Their function is intimately tied to their precise three-dimensional shape, which arises through self-organization as amino acid chains fold.

Innovation through subtle change. Dramatic innovations can result from minimal changes to protein sequences. Examples include:

- Antifreeze proteins: A few amino acid changes allow fish to survive sub-zero temperatures.

- High-altitude hemoglobin: A single amino acid change in bar-headed geese enhances oxygen binding.

- Color vision: Three amino acid changes retune opsins for green light, enabling trichromatic vision in primates.

- Antibiotic resistance: Modified transporter proteins pump antibiotics out of bacterial cells.

Astronomical solutions. Experiments show that problems like binding ATP or catalyzing a specific reaction have astronomically many protein solutions (e.g., >10^93 for ATP binding). These solutions are not isolated but form vast, interconnected "genotype networks" in the protein library. For example, globins from plants and insects, despite differing in 90% of their amino acids, still fold into nearly identical oxygen-binding shapes.

5. Regulation Circuits: Orchestrating Life's Forms and Functions

Regulation has come a long way from its murky origins in the first cells, where it balanced the growth of a membrane container with that of an RNA genome.

The conductor of life. Regulation, the precise control of gene activity, is fundamental to life's complexity and innovation. From balancing cell growth in early life to shaping complex multicellular bodies, it dictates which proteins are made, when, and in what amounts. The lactase gene in humans, for example, is regulated to switch off in adulthood for most of the world's population, but a recent mutation keeps it "on" in milk-drinking cultures.

Complex recipes for bodies. Multicellular organisms develop from a single cell into intricate bodies with specialized organs and cell types. This is achieved through sophisticated "regulatory recipes" – gene expression programs encoded in the genome. These programs involve:

- Regulator proteins: Bind to specific DNA "words" near genes to turn them on or off.

- Regulatory cascades: Regulators control other regulators in hierarchical chains.

- Regulatory circuits: Complex networks where regulators mutually influence each other's expression.

Shaping form and function. Regulatory circuits are the architects of body plans and features. For instance:

- Fruit fly segmentation: A circuit of ~15 genes creates precise segments in the embryo within hours.

- Vertebrate limbs: Hox gene circuits, conserved across diverse animals, pattern the bones of arms and legs.

- Butterfly eyespots: The distalless regulator, originally for legs, was co-opted to paint defensive eyespots on wings.

These innovations arise from changes in the "wiring" of these circuits, altering gene expression patterns.

6. Robustness: The Hidden Engine of Evolutionary Exploration

Robustness, the persistence of life’s features in the face of change.

Life's resilience. Organisms exhibit remarkable robustness, meaning their functions and phenotypes remain stable despite genetic changes. This is evident in:

- "Purposeless genes": Knocking out thousands of genes in yeast often has no observable effect, as other genes compensate.

- Metabolic detours: Blocked metabolic reactions can be bypassed by alternative pathways, like navigating a city with multiple routes.

- Protein tolerance: Over 80% of single amino acid changes in lysozyme (an antibacterial protein) do not destroy its function.

The value of disorder. Robustness allows for "neutral changes" – genetic alterations that initially have no impact on an organism's survival or reproduction. These neutral changes are not useless; they are crucial for exploration. They allow populations to accumulate genetic variation without immediate penalty, effectively "wandering" through the vast libraries of possibilities.

Genotype networks' foundation. Robustness is the fundamental principle underlying the existence of genotype networks. If every genetic change led to immediate death, synonymous genotypes would be isolated, making exploration impossible. Instead, robustness creates interconnected paths of functional genotypes, enabling continuous, meaning-preserving exploration of the genetic landscape.

7. Genotype Networks: Navigating Vast Possibility Spaces

The metabolic library is packed to its rafters with books that tell the same story in different ways.

Connected solutions. Genotype networks are vast, interconnected webs of genotypes that all produce the same phenotype (e.g., viability on glucose, a specific protein fold, a particular gene expression pattern). These networks extend far through the hyperastronomical libraries:

- Metabolic networks: Metabolisms differing in 80% of their reactions can still be viable on the same fuel.

- Protein networks: Proteins differing in 90% of their amino acids can still fold into the same shape and perform the same function.

- Regulatory networks: Circuits differing in 90% of their wiring can produce identical gene expression patterns.

Accelerating innovation. Genotype networks act as "warp drives" for evolution, dramatically accelerating the discovery of innovations. They allow populations to:

- Explore widely: Organisms can accumulate neutral changes and spread across a network without losing function.

- Access diverse neighborhoods: Different regions of a genotype network expose populations to different sets of potential new innovations.

- Shrink search space: The high-dimensional nature of these libraries means that any specific innovation is surprisingly "close" to existing functional genotypes, requiring only a tiny fraction of the library to be explored.

Eternal learning. The continuous accumulation of neutral changes along genotype networks, coupled with the diversity of accessible neighborhoods, ensures that life's innovability is near limitless. Evolution can constantly find new solutions to old problems and adapt to new challenges, without exhausting its creative potential.

8. Complexity and Standards: The Price and Enabler of Innovability

Life’s complexity and robustness increase with its exposure to environmental change.

The cost of robustness. While robustness is vital for innovation, it comes at a price: increased complexity. Simple systems are often fragile; complex systems, with their redundant parts and alternative pathways, are more robust. Nature, however, is not wasteful. What appears as "unnecessary" complexity is often crucial for survival in diverse and changing environments.

Environmental drivers of complexity:

- Metabolic flexibility: E. coli's complex metabolism (1,000+ reactions) allows it to thrive on dozens of different carbon sources. In contrast, Buchnera aphidicola, living in the stable environment of an aphid's cells, has lost 75% of its metabolic reactions and is highly fragile.

- Gene duplication: Redundant genes often specialize over time, providing robustness against environmental shifts or gene loss.

- Regulatory circuits: Complex circuits buffer development against internal molecular fluctuations and external environmental changes.

Universal standards. Life's ability to innovate combinatorially is greatly facilitated by universal molecular standards, which act as generic interfaces for building blocks. These include:

- ATP: Universal energy currency.

- Genetic code: Universal translation of DNA/RNA to protein.

- Peptide bond: Standardized chemical link for all amino acids in proteins.

- DNA binding sites: Standardized "words" for regulatory proteins.

These standards allow for mindless recombination, enabling the vast exploration of genotype networks without requiring "ingenuity."

9. Nature's Blueprint for Technological Innovation

If the warp drives that accelerate nature’s innovation could be put to work in human technology, robotic or otherwise, then the first Cambrian explosion may not have been the last.

Parallels in innovation. Technological innovation shares striking similarities with biological evolution:

- Trial and error: Edison's 10,000 failed light bulb filaments, or the constant iteration in software development.

- Populations/Crowdsourcing: Major inventions are rarely solitary efforts; they involve teams and competitive exploration.

- Multiple origins: Many inventions (e.g., calculus, steam engine, jet engine) were developed independently by multiple individuals.

- Exaptation/Co-option: Old technologies are repurposed for new uses (wine press to printing press, radar to microwave oven).

- Combinatorial nature: New technologies combine existing components (jet engine's compressor, combustion chamber, turbine).

Evolutionary algorithms. Computer scientists mimic biological evolution with "evolutionary algorithms" that use mutation and selection to solve complex problems like the traveling salesman problem. While powerful for optimization, they often lack the combinatorial power for truly revolutionary design.

The promise of digital circuits. Programmable hardware, like the modular robot YaMoR, offers a technological analog to biological genotype networks. Digital circuits, built from standardized logic gates and generic connections, form vast "circuit libraries" that exhibit:

- Circuit networks: Circuits with vastly different wiring can compute the same logic function.

- Diverse neighborhoods: Different wiring patterns lead to different accessible new functions.

- Complexity for innovability: More complex circuits (with more gates/wires) are more robust to changes and thus more innovable.

This suggests that applying the principles of genotype networks could enable future technologies to learn and innovate with unprecedented speed and creativity.

10. The Mathematical Reality of Life's Hidden Architecture

Does that mean they exist only in our imagination? Did we discover them or invent them?

Mathematics as reality. The hidden architecture of life – its hyperastronomical libraries, genotype networks, and the principles of robustness and combinatorial innovation – are not merely metaphors. They are mathematical concepts, revealed through the "unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences." This deep congruence between mathematical theorems and physical reality suggests that these structures are discovered, not invented.

Beyond human intuition. These mathematical realities exist in high-dimensional spaces, far beyond our intuitive grasp. Just as we cannot directly perceive the four legs of a galloping horse leaving the ground without Muybridge's zoopraxiscope, we cannot perceive genotype networks without the tools of computational biology.

A source older than life. The self-organization of genotype networks, driven by the simple principle of robustness, is a phenomenon that predates life itself. It is a fundamental property of complex systems, akin to the gravitational forces that shape galaxies. This hidden architecture is the timeless, eternal source of life's creativity, a Platonic realm whose faint reflection we observe in the diversity and adaptability of the living world.

Last updated:

Review Summary

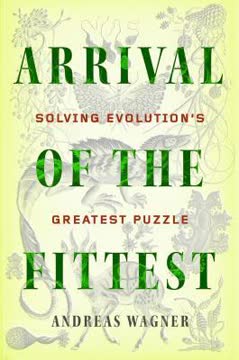

Arrival of the Fittest by Andreas Wagner explores how life innovates beyond random mutation. Wagner argues that while natural selection explains survival of the fittest, it doesn't explain their arrival. He presents evidence that metabolic systems, protein interactions, and gene regulation networks possess "genotype networks" allowing organisms to efficiently search vast genetic possibilities. Reviewers praise Wagner's research and mathematical insights but note mixed accessibility—some find it repetitive and dense, especially for lay readers, while scientists appreciate the systems biology perspective. The book's central concept of robustness and innovability addresses evolution's speed problem effectively, though some criticize verbose writing and overused metaphors.

Similar Books