Key Takeaways

1. The World Divided: Developed vs. Dependent

We are therefore in 1880 dealing not so much with a single world, as with two sectors combined together into one global system: the developed and the lagging, the dominant and the dependent, the rich and the poor.

Global transformation. By the 1880s, the world was genuinely global, more densely populated, and increasingly interconnected by trade, capital, and communication. However, this globalization also led to a stark division between a smaller, "developed" sector, primarily in Europe and its overseas settlements, and a much larger, "lagging" or "dependent" sector. This disparity was not merely economic but also technological and political, with the advanced world possessing superior armaments and organizational capacity.

Widening gap. The economic gap between these two worlds widened dramatically during this period. While per capita GNP in "developed countries" was roughly double that of the "Third World" in 1880, it soared to over three times as high by 1913. This growing chasm was largely driven by the industrial revolution, which reinforced the dominance of Western nations and made resistance from less developed regions increasingly difficult.

European centrality. Europe remained the core of this capitalist development, accounting for a higher proportion of the world's population and industrial output than ever before. Despite the rise of the USA, major technological advances still originated primarily in Europe. This era marked the zenith of European influence, culturally and economically, shaping the destiny of the rest of the world through its expanding reach and technological superiority.

2. Capitalism's Contradictions: Depression and Concentration

In short, after the admittedly drastic collapse of the 1870s... what was at issue was not production but its profitability.

Profitability crisis. The period from 1873 to the mid-1890s, known as the "Great Depression," was characterized not by economic stagnation, but by a prolonged fall in prices, interest rates, and profits. This deflationary trend, while benefiting consumers, severely squeezed businesses, particularly in agriculture, which faced a flood of cheap imports and plummeting prices. This led to widespread agrarian discontent and mass emigration.

Responses to crisis. Capitalism responded to this profitability crisis through two main strategies: economic concentration and business rationalization.

- Economic Concentration: A trend towards larger firms, mergers, and market-controlling arrangements (e.g., American "trusts," German "cartels") emerged, challenging the ideal of free competition.

- Business Rationalization: The application of "scientific methods" to production and management, epitomized by "Taylorism," aimed to maximize output and efficiency, often by intensifying worker exploitation.

Belle Époque boom. From the mid-1890s until 1914, the global economy entered a new phase of prosperity, the "belle époque," driven by mass consumption and the growth of new industries (chemicals, electricity, automobiles). This era saw a significant redistribution of economic power, with Germany and the USA rapidly catching up to and surpassing Britain in industrial output. The state's role in the economy also grew, particularly through protectionist tariffs and support for national industries.

3. The New Imperialism: Global Partition and Economic Motives

The economic and military supremacy of the capitalist countries had long been beyond serious challenge, but no systematic attempt to translate it into formal conquest, annexation and administration had been made between the end of the eighteenth and the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Global scramble. The period 1880-1914 is defined by a "new imperialism," characterized by the formal partition of most of the world outside Europe and the Americas into colonies or spheres of influence. Africa and the Pacific were almost entirely divided among a handful of European powers, the USA, and Japan. This was a novel phenomenon, distinct from earlier forms of expansion, and was widely recognized as such by contemporaries.

Economic drivers. The primary drivers of this colonial expansion were economic, though often complex and not always immediately profitable.

- Raw Materials: New technologies (e.g., internal combustion engine) created demand for exotic raw materials like oil, rubber, and non-ferrous metals, often found exclusively in remote regions.

- Markets: The belief that "overproduction" in metropolitan countries could be solved by vast export drives to untapped colonial markets, though often disappointed, fueled expansionist policies.

- Capital Export: While most capital exports went to white-settler colonies or independent states, the pressure for secure, profitable investment contributed to the acquisition of some colonial territories.

Political and ideological motives. Beyond economics, imperialism served political and ideological functions. It became a status symbol for great powers, with nations vying for a share of the global "loot." "Social imperialism" aimed to defuse domestic discontent by offering the masses glory and a sense of identification with the imperial state, reinforcing a pervasive sense of white racial superiority. This fusion of economic, political, and ideological factors made the "new imperialism" a central and defining feature of the era.

4. Democracy's Rise and Elite's Dilemma

From the moment when the ‘real country’ began to penetrate the political enclosure of the ‘legal’ or ‘political’ country, defended by the fortifications of property and educational qualifications for voting and, in most countries, by institutionalized aristocratic privilege, the social order was at risk.

Inevitable democratization. After 1870, the democratization of state politics became inevitable, with electoral systems based on wider, often universal, male suffrage spreading across Western Europe and its settler colonies. This process, though often resisted by ruling classes, was accelerated by popular agitation and the rise of mass movements. The expansion of the electorate meant that the majority of voters would be poor, insecure, and discontented.

Elite manipulation. Faced with this new reality, ruling classes sought ways to manage and manipulate democratic politics to protect their interests and the existing social order.

- Institutional Barriers: Limiting parliamentary powers, retaining property/educational qualifications, gerrymandering, and maintaining hereditary chambers.

- Patronage and Clientelism: Using local influence and political favors to secure votes, as seen in Italy and American city politics.

- Social Reform: Introducing welfare programs (e.g., social insurance, pensions) to mitigate discontent and undermine the appeal of revolutionary movements.

New political landscape. The rise of mass politics led to the formation of mass movements and parties, often ideological in nature (e.g., religious, nationalist, socialist). This era also saw the decline of localized "notable" politics, replaced by national party organizations and the increasing use of mass propaganda and media. Despite fears of social revolution, parliamentary democracy proved surprisingly compatible with capitalist stability in most Western states before 1914, largely due to these adaptive strategies and the ability to integrate or isolate various mass movements.

5. The Proletariat Mobilizes: Class Consciousness and Socialism

The proletariat was destined – one had only to look at industrial Britain and the record of national censuses over the years – to become the great majority of the people.

Growing working class. The industrial proletariat grew dramatically across the Western world, fueled by transfers from handicrafts and agriculture. These masses, often concentrated in large factories and industrial cities, became an increasingly visible and formidable social force. Their sheer numbers and shared experience of wage labor laid the groundwork for class consciousness.

Divisions and unification. Despite significant internal divisions based on skill, occupation, origin, nationality, language, and religion, the working classes were unified by powerful forces.

- Ideology and Organization: Socialist and anarchist movements, particularly Marxism, provided a unifying ideology of class struggle and a vision of a new society. Organized trade unions and political parties (e.g., German Social Democratic Party) served as crucial vehicles for collective action and identity.

- Shared Experience: The widening gap between workers and other social strata, the visible integration of employers into an undifferentiated "plutocracy," and the daily realities of workplace conflict fostered a common sense of injustice and solidarity.

- Nation-State Framework: The national economy and the nation-state, through electoral democracy and social legislation, compelled workers to adopt a national perspective, even as they embraced internationalist ideals.

Revolutionary rhetoric vs. reformist practice. Mass socialist parties, while proclaiming revolutionary aims and the inevitable triumph of the proletariat, often found themselves engaged in reformist activities within the existing system. The "Great Depression" and the subsequent economic boom fueled both revolutionary hopes and pragmatic demands for immediate improvements. This tension between revolutionary theory and reformist practice defined much of the internal debate within the socialist movement before 1914.

6. Nationalism's Transformation: From Liberalism to the Right

Nationalism … attacks democracy, demolishes anti-clericalism, fights socialism and undermines pacifism, humanitarianism and internationalism. … It declares the programme of liberalism finished.

Nationalism's resurgence. Nationalism underwent a dramatic transformation from 1880 to 1914, shifting from its earlier association with liberal and radical movements to become an ideology increasingly embraced by the political right. This new nationalism was aggressive, xenophobic, and often linked to imperial expansion and militarism. The term "nationalism" itself emerged to describe these right-wing movements.

Ethnic and linguistic definitions. A key mutation was the growing tendency to define a nation in terms of ethnicity and, especially, language, rather than shared political ideals or historical experience. This led to demands for self-determination for virtually any group claiming to be a "nation," often aspiring to full state independence. This linguistic nationalism was largely a creation of literate elites and middle strata, who saw language as a path to professional advancement and cultural distinctiveness.

State-driven patriotism. States actively fostered national patriotism through mass elementary education and compulsory military service, aiming to forge homogenized citizens and counter other loyalties like class or religion. This "civic religion" of the state, however, often alienated those who did not belong to the official nation, leading to increased national tensions within multinational empires like Austria-Hungary and Russia. The rise of xenophobia, fueled by mass migration and social anxieties, further solidified nationalist sentiments, particularly among the middle and lower-middle classes.

7. Bourgeoisie's Identity Crisis: Leisure, Status, and Anxiety

The College is founded by the advice and counsel of the Founder’s dear wife … to afford the best education for women of the Upper and Upper Middle Classes.

Evolving lifestyle. The bourgeois lifestyle, initially characterized by puritan values and capital accumulation, evolved significantly. The ideal shifted from urban palaces to suburban houses with gardens, emphasizing private comfort over public display. This reflected a certain withdrawal from direct political engagement as democracy advanced, and a loosening of traditional moral strictures as wealth became more inherited or derived from distant investments.

Expanding middle class. The "middle class" expanded dramatically, encompassing not only traditional entrepreneurs and professionals but also a growing "lower-middle class" of salaried non-manual workers. This expansion blurred social boundaries and created a need for new markers of status and identity.

- Education: Formal education, particularly secondary and university degrees, became the primary ticket to middle-class status, signifying delayed gratification and cultural capital.

- Leisure and Sport: Organized sports, formalized in Britain and spreading globally, provided a new arena for social cohesion and distinction, with amateurism serving as a class differentiator.

Anxieties of affluence. Despite unprecedented prosperity, a sense of unease permeated parts of the bourgeoisie, particularly among intellectuals and the youth. They grappled with the perceived decline of traditional values, the rise of the "masses," and the potential for parasitism. This "fin de siècle" mood, marked by pessimism and a questioning of progress, reflected a crisis of confidence in the very foundations of their society, even as they enjoyed its material comforts.

8. Women's Emancipation: Demographic Shifts and New Roles

The restoration of woman’s self-respect is the gist of the feminist movement. The most substantial of its political victories can have no higher value than this – that they teach women not to depreciate their own sex.

Demographic transition. A profound change in women's lives in the "developed" world was the onset of the "demographic transition," marked by a sharp decline in birth rates from the 1870s. This was achieved through later marriages, increased celibacy, and the spread of birth control, driven by desires for a higher standard of living and the rising economic burden of children. This shift allowed for greater investment in fewer offspring.

Changing economic roles. Industrialization initially excluded many women, especially married ones, from the formal wage economy, reinforcing their economic dependence. However, new opportunities emerged in the tertiary sector:

- Office and Retail: The rise of clerical and shop assistant roles, often feminized, provided new employment for middle and lower-middle-class women.

- Education: Teaching became a significantly feminized profession, particularly in elementary schools.

- Domestic Service: While still a major employer, its growth stagnated, indicating a shift in female labor patterns.

Feminist movements and social change. The period saw the emergence of the "new woman" and organized feminist movements, primarily among the middle classes, campaigning for suffrage, education, and professional access. While these movements were often small and faced resistance, they were supported by socialist parties and contributed to significant legal and political gains, such as the widespread granting of women's suffrage after WWI. Sexual liberation also became a topic of discussion, reflecting a broader challenge to traditional gender roles and expectations.

9. Intellectual Upheaval: Science and Art in Crisis

There are times when man’s entire way of apprehending and structuring the universe is transformed in a fairly brief period of time, and the decades which preceded the First World War were one of these.

Crisis of certainty. The decades before WWI witnessed a profound intellectual transformation, particularly in the natural sciences, challenging the Newtonian-Galilean mechanical universe and the intuitive understanding of reality. This crisis was marked by:

- Mathematics: The emergence of non-Euclidean geometries and Cantor's work on infinite magnitudes, which defied intuition and led to a re-evaluation of mathematical foundations.

- Physics: The "crisis of the ether" and the advent of quantum theory (Planck, 1900) and relativity (Einstein, 1905), which shattered classical physics and introduced concepts remote from common sense.

Artistic rebellion. The arts also experienced a deep identity crisis, with a growing divergence between creative artists and the public. The avant-garde, embracing "modernity" and "realism," sought new forms of expression, often rejecting traditional conventions and values.

- Art Nouveau: A revolutionary, anti-historicist style that attempted to fuse art and life, but ultimately struggled with the implications of machine production.

- Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Expressionism: Movements that explored the subjective nature of reality, the deconstruction of form, and emotional expression, often alienating the mainstream public.

Mass culture's rise. Simultaneously, a parallel cultural revolution was unfolding in mass entertainment, driven by technology and the mass market. The cinema, born in 1895, rapidly became a global phenomenon, offering accessible entertainment and developing a universal visual language, largely independent of the high-cultural avant-garde. This new art form, profoundly capitalist in its production, would come to dominate 20th-century culture.

10. Revolution on the Periphery: Empires in Collapse

In short, for the vast area of the globe which thus constituted what Lenin in 1908 acutely called ‘combustible material in world politics’, the idea that somehow or other, but for the unforeseen and avoidable intervention of catastrophe in 1914, stability, prosperity and liberal progress would have continued, has not even the most superficial plausibility.

Global earthquake zone. While Western Europe enjoyed relative stability, vast areas of the world, particularly the ancient empires stretching from China to the Habsburgs, were in a state of impending or actual revolution. These archaic political structures, weakened by internal contradictions and external imperialist pressure, were seen as obsolete and doomed.

Imperial disintegration. The pressure of Western imperialism accelerated the collapse of these empires:

- Persia: Caught between Russian and British ambitions, experienced a constitutional revolution in 1906, but remained de facto dependent.

- China: Weakened by internal rebellions and foreign incursions, the Qing Empire fell in 1911, leading to a period of warlordism rather than a stable new regime.

- Ottoman Empire: Long in decline, faced nationalist revolts in the Balkans and increasing Western encroachment in North Africa and the Middle East. The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 failed to save the empire, leading to its eventual dissolution and the rise of Turkish nationalism.

- Mexico: A dependent state, experienced a major social revolution from 1910, driven by agrarian discontent and the destabilizing effects of integration into the US economy.

Russia: The central fuse. The Tsarist Empire, a "great power" straddling Europe and Asia, was perhaps the most volatile. Rapid state-sponsored industrialization created a large, revolutionary proletariat, while the peasantry remained deeply discontented. The humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) triggered the 1905 Revolution, which, though suppressed, revealed the fragility of tsarism and the revolutionary potential of workers and peasants. Lenin's analysis of a "bourgeois revolution achieved by proletarian means" highlighted the weakness of the Russian bourgeoisie and the unique role of the working class.

11. From Peace to Global War: The Inevitable Catastrophe

The most that can be claimed is that at a certain point in the slow slide towards the abyss, war seemed henceforth so inevitable that some governments decided that it might be best to choose the most favourable, or least unpropitious, moment for launching hostilities.

Illusions of peace. Despite a century of relative peace among European powers (1815-1914), the outbreak of World War I in 1914 was a profound shock, even to those who initiated it. Peace was the expected norm, and previous international crises, even in the volatile Balkans, had been managed. However, the underlying belief that a major war was "impossible" was deeply ingrained, leading to a collective disbelief when it finally erupted.

Arms race and industrialization of war. The period saw an accelerating arms race, driven by technological advancements in weaponry and naval power. Military expenditures soared, creating a symbiotic relationship between governments and giant armaments industries. This "industrialization of warfare" made conflict vastly more destructive and expensive, as predicted by figures like Ivan Bloch, though military planners largely ignored such warnings.

Deteriorating international situation. Europe's division into two rigid, hostile blocs—the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy) and the Triple Entente (France, Russia, Britain)—created an increasingly unstable international system. The crucial factor was Britain's unexpected alignment with France and Russia against Germany, driven by:

- Global Power Shifts: Britain's declining global dominance and the rise of new industrial powers, particularly Germany, challenged the Pax Britannica.

- German Naval Expansion: Germany's ambition to build a large battle-fleet was perceived by Britain as an existential threat to its naval supremacy and imperial lifelines.

- Imperialist Rivalries: While colonial conflicts were usually contained, they contributed to the formation of these belligerent blocs.

Domestic and international crises merge. In the years leading up to 1914, domestic political crises in several powers (Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany) merged with international tensions. Governments, facing internal unrest and the challenges of mass politics, were tempted to seek external triumphs or felt compelled to act decisively, fearing that delay would worsen their strategic position. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, a seemingly minor incident, triggered an irreversible chain of events, as powers, locked into their alliances and mobilization plans, slid into a war that none truly desired but all felt was inevitable.

12. The End of an Era: Legacy of Contradictions

The twentieth century has seen too many moments of liberation and social ecstasy to have much confidence in their permanence.

Catastrophe and transformation. The First World War marked the end of the "Age of Empire" and the liberal bourgeois world order, ushering in an era of unprecedented global upheavals and human cataclysms. The scale of death, displacement, and social convulsion after 1914 was unimaginable by 19th-century standards, fundamentally altering humanity's perception of progress and the future.

Bolshevism's shadow. The war led to the collapse of empires and the rise of the first communist regime in Russia, which profoundly shaped 20th-century world politics. The threat of "Bolshevism" dominated international relations, forcing capitalist states to adapt and implement significant reforms, often adopting state-managed economic policies that would have been unthinkable before 1914. This period saw the temporary retreat of liberal democracy in much of Europe, replaced by authoritarian regimes.

Enduring legacies. Despite the dramatic shifts, the Age of Empire left a lasting historical landscape:

- Ideological Divide: The world's division into socialist and capitalist blocs.

- Globalized Politics: The proliferation of "nation-states" (many of modest size) from decolonization, largely reproducing colonial frontiers and adopting Western political models.

- Social Change: The continued emancipation of women and the transformation of traditional family structures.

- Mass Culture: The birth of modern mass media and entertainment, particularly film, which revolutionized the arts and global communication.

Lost certainty, persistent hope. The 20th century shattered the 19th-century's utopian certainty in inevitable progress, replacing it with an awareness of potential apocalypse. Yet, despite the disillusionment, the human capacity for hope and the pursuit of a better society persisted. The Age of Empire, with its contradictions and its promise, laid the groundwork for a future that was both unforeseen and, in its material and intellectual achievements, undeniably impressive, even if the path to utopia remained uncertain.

Last updated:

Review Summary

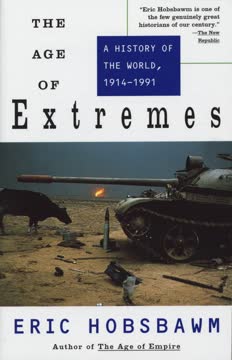

The Age of Empire, 1875–1914 receives strong praise (4.26/5) for its comprehensive analysis of the pre-WWI era through a Marxist lens. Readers appreciate Hobsbawm's synthesis of economic, political, social, and cultural developments, examining imperialism, capitalism's expansion, democracy's rise, and nationalism's solidification. Many find it dense and requiring prior historical knowledge, but value its thematic organization and connections between seemingly disparate events. Critics note its Eurocentric perspective and deterministic framework. The book effectively explains WWI's complex causes beyond Franz Ferdinand's assassination, showing how peace-era contradictions led to catastrophe.

Modern History: The Four Ages Series

Similar Books